Nomadic Infrastructure Design for AI Workloads

![A nomadic server hunting down wild GPUs in order to save money on its cloud computing bill. Image generated with Flux [dev] from Black Forest Labs on fal.ai](/blog/assets/images/nomadic-compute-78b3795789f3860483e46f565f6841c1.webp)

A nomadic server hunting down wild GPUs in order to save money on its cloud computing bill. Image generated with Flux [dev] from Black Forest Labs on fal.ai.

Taco Bell is a miracle of food preparation. They manage to have a menu of dozens of items that all boil down to permutations of 8 basic items: meat, cheese, beans, vegetables, bread, and sauces. Those basic fundamentals are combined in new and interesting ways to give you the crunchwrap, the chalupa, the doritos locos tacos, and more. Just add hot water and they’re ready to eat.

Even though the results are exciting, the ingredients for them are not. They’re all really simple things. The best designed production systems I’ve ever used take the same basic idea: build exciting things out of boring components that are well understood across all facets of the industry (eg: S3, Postgres, HTTP, JSON, YAML, etc.). This adds up to your pitch deck aiming at disrupting the industry-disrupting industry.

A bunch of companies want to sell you inference time for your AI workloads or the results of them inferencing AI workloads for you, but nobody really tells you how to make this yourself. That’s the special Mexican Pizza sauce that you can’t replicate at home no matter how much you want to be able to.

Today, we’ll cover how you, a random nerd that likes reading architectural articles, should design a production-ready AI system so that you can maximize effectiveness per dollar, reduce dependency lock-in, and separate concerns down to their cores. Buckle up, it’s gonna be a ride.

The industry uses like a billion different terms for “unit of compute that has access to a network connection and the ability to store things for some amount of time” that all conflict in mutually incompatible ways. When you read “workload”, you should think about some program that has network access to some network and some amount of storage through some means running somewhere, probably in a container.

The fundamentals of any workload

At the core, any workload (computer games, iPadOS apps, REST APIs, Kubernetes, $5 Hetzner VPSen, etc.) is a combination of three basic factors:

- Compute, or the part that executes code and does math

- Network, or the part that lets you dial and accept sockets

- Storage, or the part that remembers things for next time

In reality, these things will overlap a little (compute has storage in the form of ram, some network cards run their own Linux kernel, and storage is frequently accessed over the network), but that still very cleanly maps to the basic things that you’re billed for in the cloud:

- Gigabyte-core-seconds of compute

- Gigabytes egressed over the network

- Gigabytes stored in persistent storage

And of course, there’s a huge money premium for any of this being involved in AI anything because people will pay. However, let’s take a look at that second basic thing you’re billed for a bit closer:

- Gigabytes egressed over the network

Note that it’s egress out of your compute, not ingress to your compute. Providers generally want you to make it easy to put your data into their platform and harder to get the data back out. This is usually combined with your storage layer, which can make it annoying and expensive to deal with data that is bigger than your local disk. Your local disk is frequently way too small to store everything, so you have to make compromises.

What if your storage layer didn’t charge you per gigabyte of data you fetched out of it? What classes of problems would that allow you to solve that were previously too expensive to execute on?

Tigris is object storage with zero egress fees.

If you put your storage in a service that is low-latency, close to your servers, and has no egress fees, then it can actually be cheaper to pull things from object storage just-in-time to use them than it is to store them persistently.

Storage that is left idle is more expensive than compute time

In serverless (Lambda) scenarios, most of the time your application is turned off. This is good. This is what you want. You want it to turn on when it’s needed, and turn back off when it’s not. When you do a setup like this, you also usually assume that the time it takes to do a cold start of the service is fast enough that the user doesn’t mind.

Let’s say that your AI app requires 16 gigabytes of local disk space for your Docker image with the inference engine and the downloaded model weights. In some clouds (such as Vast.ai), this can cost you upwards of $4-10 per month to have the data sitting there doing nothing, even if the actual compute time is as low as $0.99 per hour. If you’re using Flux [dev] (12 billion parameters, 25 GB of weight bytes) and those weights take 5 minutes to download, this means that you are only spending $0.12 waiting things to download. If you’re only doing inference in bulk scenarios where latency doesn’t matter as much, then it can be much, much cheaper to dynamically mint new instances, download the model weights from object storage, do all of the inference you need, and then slay those instances off when you’re done.

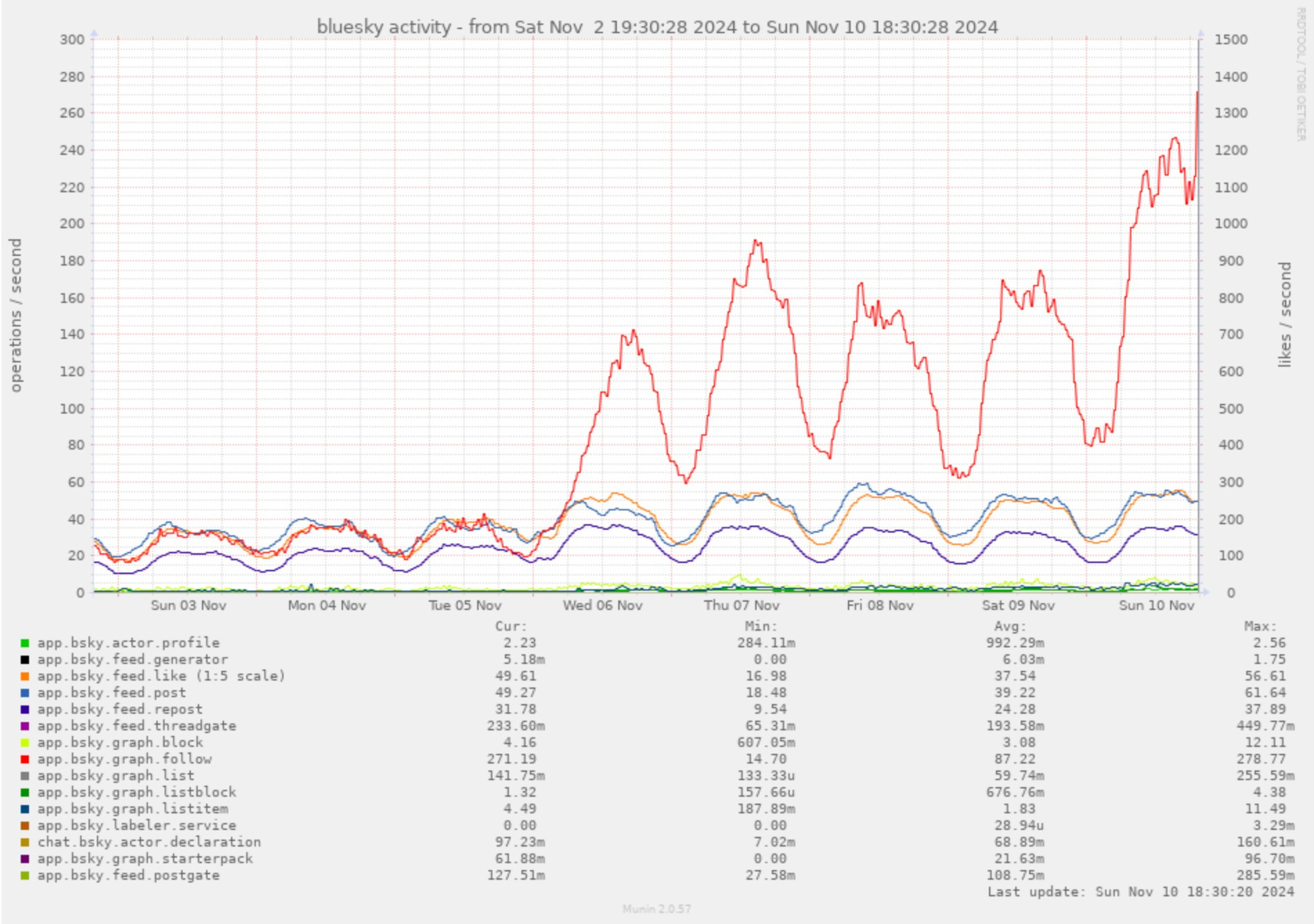

A graph showing Bluesky user activity. Note how there's a sinusodal pattern and user operations have a daily peak before falling down to zero as everyone goes to sleep. This kind of sinusodal pattern is something you see all over the industry and is generally a sign of a healthy service. Imagine scaling things down as the graph trends downwards and then back up as the graph trends upwards.

Most of the time, any production workload’s request rate is going to follow a sinusodal curve where there’s peak usage for about 8 hours in the middle of the day and things will fall off overnight as everyone goes to bed. If you spin up AI inference servers on demand following this curve, this means that the first person of the day to use an AI feature could have it take a bit longer for the server to get its coffee, but it’ll be hot’n’ready for the next user when they use that feature.

You can even cheat further with optional features such that the first user doesn’t actually see them, but it triggers the AI inference backend to wake up for the next request.

It may not be your money, but the amounts add up

When you set up cloud compute, it’s really easy to fall prey to the siren song of the seemingly bottomless budget of the corporate card. At a certain point, we all need to build sustainable business as the AI hype wears off and the free tier ends. However, thanks to the idea of Taco Bell infrastructure design, you can reduce the risk of lock-in and increase flexibility between providers so you can lower your burn rate.

In many platforms, data ingress is free. Data egress is where they get you. It’s such a problem for businesses that the EU has had to step in and tell providers that people need an easy way out. Every gigabyte of data you put into those platforms is another $0.05 that it’ll cost to move away should you need to.

This doesn’t sound like an issue, because the CTO negotiating dream is that they’ll be able to play the “we’re gonna move our stuff elsewhere” card and instantly win a discount and get a fantastic deal that will enable future growth or whatever.

This is a nice dream.

In reality, the sales representative has a number in big red letters in front of them. This number is the amount of money it would cost for you to move your 3 petabytes of data off of their cloud. You both know you’re stuck with eachother, and you’ll happily take an additional measly 5% discount on top of the 10% discount you negotiated last year. We all know that the actual cost of running the service is 15% of even that cost; but the capitalism machine has to eat somehow, right?

On the nature of dependencies

Let’s be real, dependencies aren’t fundamentally bad things to have. All of us have a hard dependency on the Internet, amd64 CPUs, water, and storage. Everything’s a tradeoff. The potentially harmful part comes in when your dependency locks you in so you can’t switch away easily.

This is normally pretty bad with traditional compute setups, but can be extra insidious with AI workloads. AI workloads make cloud companies staggering amounts of money, so they want to make sure that you keep your AI workloads on their servers as much as possible so they can extract as much revenue out of you as possible. Combine this with the big red number disadvantage in negotiations, and you can find yourself backed into a corner.

Strategic dependency choice

This is why picking your dependencies is such a huge thing to consider. There’s a lot to be said about choosing dependencies to minimize vendor lock-in, and that’s where the Taco Bell infrastructure philosophy comes in:

- Trigger compute with HTTP requests that use well-defined schemata.

- Find your target using DNS.

- Store things you want to keep in Postgres or object storage.

- Fetch things out of storage when you need them.

- Mint new workers when there is work to be done.

- Slay those workers off when they’re not needed anymore.

If you follow these rules, you can easily make your compute nomadic between services. Capitalize on things like Kubernetes (the universal API for cloud compute, as much as I hate that it won), and you make the underlying clouds an implementation detail that can be swapped out as you find better strategic partnerships that can offer you more than a measly 5% discount.

Just add water.

How AI models become dependencies

There's an extra evil way that AI models can become production-critical dependencies. Most of the time when you implement an application that uses an AI model, you end up encoding "workarounds" for the model into the prompts you use. This happens because AI models are fundamentally unpredictable and unreliable tools that sometimes give you the output you want. As a result though, changing out models sounds like it's something that should be easy. You just change out the model and then you can take advantage of better accuracy, new features like tool use, or JSON schema prompting, right?

In many cases, changing out a model will result in a service that superficially looks and functions the same. You give it a meeting transcript, it tells you what the action items are. The problem comes in with the subtle nuances of the je ne sais quoi of the experience. Even subtle differences like the current date being in the month of December can drastically change the quality of output. A recent paper from Apple concluded that adding superficial details that wouldn't throw off a human can severely impact the performance of large language models. Heck, they even struggle or fall prey to fairly trivial questions that humans find easy, such as:

- How many r's are in the word "strawberry"?

- What's heavier: 2 pounds of bricks, one pound of heavy strawberries, or three pounds of air?

If changing the placement of a comma in a prompt can cause such huge impacts to the user experience, what would changing the model do? What would being forced to change the model because the provider is deprecating it so they can run newer models that don't do the job as well as the model you currently use? This is a really evil kind of dependency that you can only get when you rely on cloud-hosted models. By controlling the weights and inference setups for your machines, you have a better chance of being able to dictate the future of your product and control all parts of the stack as much as possible.

How it’s made prod-ready

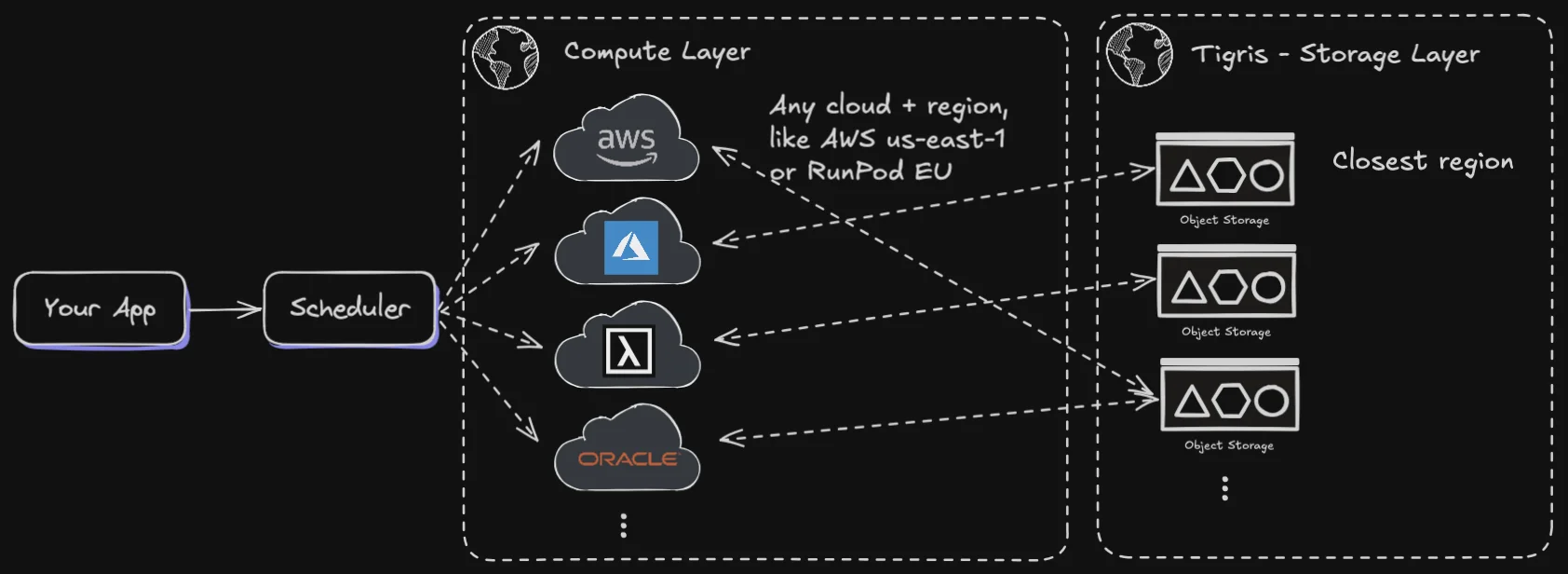

Like I said earlier, the three basic needs of any workload are compute, network, and storage. Production architectures usually have three basic planes to support them:

- The compute plane, which is almost certainly going to be ether Docker or Kubernetes somehow.

- The network plane, which will be a Virtual Private Cloud (VPC) or overlay network that knits clusters together.

- The storage plane, which is usually the annoying exercise left to the reader, leading you to make yet another case for either using NFS or sparkly NFS like Longhorn.

Storage is the sticky bit; it’s not really changed since the beginning. You either use a POSIX-compatible key-value store or an S3 compatible key-value store. Both are used in practically the same ways that the framers intended in the late 80’s and 2009 respectively. You chuck bytes into the system with a name, and you get the bytes back when you give the name.

Storage is the really important part of your workloads. Your phone would not be as useful if it didn’t remember your list of text messages when you rebooted it. Many applications also (reasonably) assume that storage always works, is fast enough that it’s not an issue, and is durable enough that they don’t have to manually make backups.

What about latency? Human reaction time is about 250 milliseconds on average. It takes about 250 milliseconds for a TCP session to be established between Berlin and us-east-1. If you move your compute between providers, is your storage plane also going to move data around to compensate?

How will your storage plane adapt to your needs instead of your needs adapting to your storage plane?

If your storage plane doesn’t have egress costs and stores your data close to where it’s used, this eliminates a lot of local storage complexity, at the cost of additional compute time spent waiting to pull things and the network throughput for them to arrive. Somehow compute is cheaper than storage in anno dominium two-thousand twenty-four. No, I don’t get how that happened either.

Pass-by-reference semantics for the cloud

Part of the secret for how people make these production platforms is that they cheat: they don’t pass around values as much as possible. They pass a reference to that value in the storage plane. When you upload an image to the ChatGPT API to see if it’s a picture of a horse, you do a file upload call and then an inference call with the ID of that upload. This makes it easier to sling bytes around and overall makes things a lot more efficient at the design level. This is a lot like pass-by-reference semantics in programming languages like Java or a pointer to a value in Go.

The big queue

The other big secret is that there’s a layer on top of all of the compute: an orchestrator with a queue.

This is the rest of the owl that nobody talks about. Just having compute, network, and storage is not good enough; there needs to be a layer on top that spreads the load between workers, intelligently minting and slaying them off as reality demands.

Okay but where’s the code?

Yeah, yeah, I get it, you want to see this live and in action. I don’t have an example totally ready yet, but in lieu of drawing the owl right now, I can tell you what you’d need in order to make it a reality on the cheap.

Let’s imagine that this is all done in one app, let’s call it orodayagzou (c.f. Ôrödyagzou, Ithkuil for “synesthesia”). This app is both a HTTP API and an orchestrator. It manages a pool of worker nodes that do the actual AI inferencing.

So let’s say a user submits a request asking for a picture of a horse. That’ll come in to the right HTTP route and it has logic like this:

type ScaleToZeroProxy struct {

cfg Config

ready bool

endpointURL string

instanceID int

lock sync.RWMutex

lastUsed time.Time

}

func (s *ScaleToZeroProxy) ServeHTTP(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

s.lock.RLock()

ready := s.ready

s.lock.RUnlock()

if !ready {

// TODO: implement instance creation

}

s.lock.RLock()

defer s.lock.RUnlock()

u, err := url.Parse(s.endpointURL)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

u.Path = r.URL.Path

u.RawQuery = r.URL.RawQuery

next := httputil.NewSingleHostReverseProxy(u)

next.ServeHTTP(w, r)

s.lock.Lock()

s.lastUsed = time.Now()

s.lock.Unlock()

}

This is a simple little HTTP proxy in Go, it has an endpoint URL and an instance ID in memory, some logic to check if the instance is “ready”, and if it’s not then to create it. Let’s mint an instance using the Vast.ai CLI. First, some configuration:

const (

diskNeeded = 36

dockerImage = "reg.xeiaso.net/runner/sdxl-tigris:latest"

httpPort = 5000

modelBucketName = "ciphanubakfu" // lojban: test-number-bag

modelPath = "glides/ponyxl"

onStartCommand = "python -m cog.server.http"

publicBucketName = "xe-flux"

searchCaveats = `verified=False cuda_max_good>=12.1 gpu_ram>=12 num_gpus=1 inet_down>=450`

// assume awsAccessKeyID, awsSecretAccessKey, awsRegion, and awsEndpointURLS3 exist

)

type Config struct {

diskNeeded int // gigabytes

dockerImage string

environment map[string]string

httpPort int

onStartCommand string

}

Then we can search for potential machines with some terrible wrappers to the CLI:

func runJSON[T any](ctx context.Context, args ...any) (T, error) {

return trivial.andThusAnExerciseForTheReader[T](ctx, args)

}

func (s *ScaleToZeroProxy) mintInstance(ctx context.Context) error {

s.lock.Lock()

defer s.lock.Unlock()

candidates, err := runJSON[[]vastai.SearchResponse](

ctx,

"vastai", "search", "offers",

searchCaveats,

"-o", "dph+", // sort by price (dollars per hour) increasing, cheapest option is first

"--raw", // output JSON

)

if err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("can't search for instances: %w", err)

}

// grab the cheapest option

candidate := candidates[0]

contractID := candidate.AskContractID

slog.Info("found candidate instance",

"contractID", contractID,

"gpuName", candidate.GPUName,

"cost", candidate.Search.TotalHour,

)

// ...

}

Then you can try to create it:

func (s *ScaleToZeroProxy) mintInstance(ctx context.Context) error {

// ...

instanceData, err := runJSON[vastai.NewInstance](

ctx,

"vastai", "create", "instance",

contractID,

"--image", s.cfg.dockerImage,

// dump ports and envvars into format vast.ai wants

"--env", s.cfg.FormatEnvString(),

"--disk", s.cfg.diskNeeded,

"--onstart-cmd", s.cfg.onStartCommand,

"--raw",

)

if err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("can't create new instance: %w", err)

}

slog.Info("created new instance", "instanceID", instanceData.NewContract)

s.instanceID = instanceData.NewContract

// ...

Then collect the endpoint URL:

func (s *ScaleToZeroProxy) mintInstance(ctx context.Context) error {

// ...

instance, err := runJSON[vastai.Instance](

ctx,

"vastai", "show", "instance",

instanceData.NewContract,

"--raw",

)

if err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("can't show instance %d: %w", instanceData.NewContract, err)

}

s.EndpointURL = fmt.Sprintf(

"http://%s:%d",

instance.PublicIPAddr,

instance.Ports[fmt.Sprintf("%d/tcp", s.cfg.httpPort)][0].HostPort,

)

return nil

}

And then finally wire it up and have it test if the instance is ready somehow:

func (s *ScaleToZeroProxy) ServeHTTP(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

// ...

if !ready {

if err := s.mintInstance(r.Context()); err != nil {

slog.Error("can't mint new instance", "err", err)

http.Error(w, err.Error(), http.StatusInternalServerError)

return

}

t := time.NewTicker(5 * time.Second)

defer t.Stop()

for range t.C {

if ok := s.testReady(r.Context()); ok {

break

}

}

}

// ...

Then the rest of the logic will run through, the request will be passed to the GPU instance and then a response will be fired. All that’s left is to slay the instances off when they’re unused for about 5 minutes:

func (s *ScaleToZeroProxy) maybeSlayLoop(ctx context.Context) {

t := time.NewTicker(5 * time.Minute)

defer t.Stop()

for {

select {

case <-t.C:

s.lock.RLock()

lastUsed := s.lastUsed

s.lock.RUnlock()

if lastUsed.Add(5 * time.Minute).Before(time.Now) {

if err := s.slay(ctx); err != nil {

slog.Error("can't slay instance", "err", err)

}

}

case <-ctx.Done():

return

}

}

}

Et voila! Run maybeSlayLoop in the background and implement the slay()

method to use the vastai destroy instance command, then you have yourself

nomadic compute that makes and destroys itself on demand to the lowest bidder.

Of course, any production-ready implementation would have limits like “don’t

have more than 20 workers” and segment things into multiple work queues. This is

all really hypothetical right now, I wish I had a thing to say you could

kubectl apply and use right now, but I don’t.

I’m going to be working on this this on my Friday streams on Twitch until it’s done. I’m going to implement it from an empty folder and then work on making it a Kubernetes operator to run any task you want. It’s going to involve generative AI, API reverse engineering, eternal torment, and hopefully not getting banned from the providers I’m going to be using. It should be a blast!

Conclusion

Every workload involves compute, network, and storage on top of production’s compute plane, network plane, and storage plane. Design your production clusters to take advantage of very well-understood fundamentals like HTTP, queues, and object storage so that you can reduce your dependencies to the bare minimum. Make your app an orchestrator of vast amounts of cheap compute so you don’t need to pay for compute or storage that nobody is using while everyone is asleep.

This basic pattern is applicable to just about anything on any platform, not just AI or not just with Tigris. We hope that by publishing this architectural design, you’ll take it to heart when building your production workloads of the future so that we can all use the cloud responsibly. Certain parts of the economics of this pattern work best when you have free (or basically free) egress costs though.

We’re excited about building the best possible storage layer based on the lessons learned building the storage layer Uber uses to service millions of rides per month. If you try us and disagree, that’s fine, we won’t nickel and dime you on the way out because we don’t charge egress costs.

When all of these concerns are made easier, all that’s left for you is to draw the rest of the owl and get out there disrupting industries.

Make a global bucket with no egress fees